Puffins & Seabirds

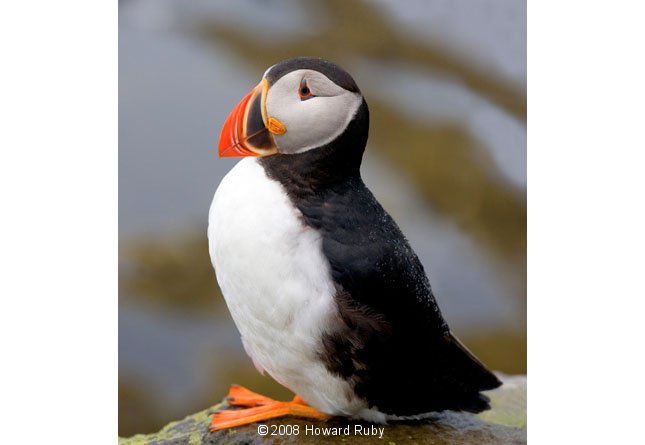

The horned puffin gets its name from the small, horn-like “eye-lash”that extends above the eye. The tufted puffin is the largest puffin and is primarily black in color with only a white mask on its face. The bright colors on the puffin’s beak and legs appear only during mating season. All puffins dive, fish, and sleep out at sea for months at a time.

Puffins have waterproof feathers and the ability to drink salt water and catch food. They “fly” both in the air and the sea. They can dive down to 200 feet and stay under water for up to a minute, scooping up small fish one-by-one. Puffins hold the fish crosswise in their beaks with their tongue while diving for more. The average catch is around 10 fish per trip, but they can easily carry up to 40 fish at one time. The biggest haul on record is 62 fish at once!

In early summer, puffins gather in the water near rocky coastlines. Each bird chooses a mate—usually the same one as the year before. The pairs mate in the water and then come ashore to prepare for parenthood. Mates share all of the nesting and parenting duties, and they even bring flowers to each other. Each pair needs a burrow to call home. Many times, puffins will return to the same nest each year and clean it before laying an egg. New mates will look for a snug crack between the rocks, or they will dig their own hole about three feet deep. They use their bills as shovels and clear away loose dirt with their feet. At the end of the tunnel, they hollow out two rooms: a toilet room and a “nursery” that they line with grass and soft feathers.

Deep inside her cozy burrow, each female lays a single egg. For about six weeks, she and her mate take turns keeping the egg warm and safe. Gulls are their biggest worry—they will try to steal and eat puffin eggs and chicks. When the egg hatches, out pops a fluffy, black puffin chick, called a “puffling.” For two more months, the puffling stays deep in the burrow, safe from predators. Mom and Dad bring meals of fish up to ten times a day. The puffling grows up on these fishy meals. Then, one night, the young puffin comes out of its burrow at last. Under cover of darkness (when the gulls are asleep), it heads for the edge of the cliff. Leaping into the water, it swims away to begin life on its own. It will be five years before the puffin will return to its hatchery to raise its own puffling.

A puffin colony is crowded with many pairs of birds. Males defend their burrows—and their females—from rivals. While on guard, a male slowly paces back and forth. If another male comes too close, he puffs up his body, opens his bill, and stomps his feet. If the trespasser doesn’t get the message, a wrestling match begins. The two birds lock bills and try to topple each other using their feet and wings. Often, other puffins gather around to watch the fight. Even though puffins will fight to protect their burrows and their mates, they are very social birds that will often “chat” with each other after a day of fishing.

Puffins live 20 years or more and they are experiencing new challenges as a result of global warming. As ocean temperatures warm, many fish species have begun traveling north to colder waters. This is greatly depleting the puffins of their traditional food supply surrounding their nesting colonies, making it difficult to feed their young.

Many scientists who study seabirds are working hard to learn all they can about global warming. They hope to use what they learn to help puffins and other seabirds.